From the Editor: “Countries like Finland (“Nokia-land”) keep producing top electronics engineers because they focus on making complex radio technology practical, efficient, and affordable. Modern radars, mobile networks, and defence systems all rely on smart antenna arrays that can electronically “aim” radio waves and work across many frequencies. As these systems evolve, engineers must make antennas smaller, lighter, cheaper, and more flexible—without losing performance. This research shows how Finnish-style innovation tackles that challenge: using clever manufacturing methods, new materials, and tightly integrated electronics to build high-performance antennas that are lighter, simpler, and powerful enough for next-generation communications and radar systems.”

Petteri Pulkkinen’s doctoral thesis at Aalto University tackles one of the most stubborn, high‑stakes problems in modern wireless: how to make radar and communications share spectrum, often the same hardware and waveforms, without stepping on each other’s toes.

His answer is a rigorous, learn‑as‑you‑go approach built on model‑based reinforcement learning (MBRL) and formalized through constrained partially observable Markov decision processes (C‑POMDPs). In plain terms, he builds an intelligent controller that knows enough physics to be data‑efficient yet still learns online from the world’s messiness.

The result: ISAC systems that adapt in real time to interference, targets, channels, and uncertainty, while providing theoretical performance guarantees rarely seen in learning‑driven radio.

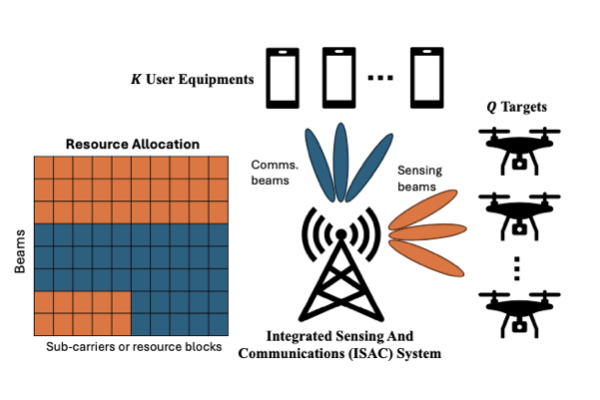

Modern radars and wireless networks are converging multicarrier waveforms (think OFDM and its cousins), large antenna arrays, and adaptive transceivers are now common to both. At the same time, spectrum is congested, contested, and politically charged. Traditional “solve‑it‑once” optimization struggles here because it presumes stable, perfectly known models. Pulkkinen reframes the problem: treat ISAC as a sequential decision process under uncertainty, let the system learn the environment online, and co‑optimize waveforms, beams, and power with both sensing and communications objectives in mind.

The Core Architecture

At the heart of the thesis is a C‑POMDP formulation. It captures:

- Actions: which subcarriers (or resource blocks) and beams to use, and with what power, for sensing and for communications.

- States: time‑varying target dynamics and radio channels, plus interference and noise.

- Observations: noisy detections, channel measurements, and environment statistics.

- Utilities & Constraints: long‑term sensing gains (e.g., mutual information, detection probability, tracking error) while meeting communications quality (e.g., rate) constraints.

Pulkkinen’s decision‑making loop is model‑based: it learns a predictive model of environment dynamics (e.g., how interference and channel quality evolve) and plans with that model at each time step. Two controller designs anchor the work:

- Myopic control – surprisingly powerful under realistic assumptions (e.g., action‑independent state transitions and observations): it maximizes the one‑step expected utility subject to constraints and, under those conditions, is provably optimal. He also derives performance bounds that quantify how quickly the learned model and resulting policy converge.

- Pseudo‑myopic control – for harder, partially observable cases where actions influence what you learn next. Here, he injects exploration directly into the utility via principled regularization (e.g., Thompson sampling and optimism‑in‑the‑face‑of‑uncertainty ideas), achieving practical exploration in large joint frequency‑beamspace decisions without the crippling complexity of full look‑ahead planning.

Guarantees on Learning and Control

The thesis doesn’t stop at algorithms; it proves things that practitioners care about:

- Model‑learning convergence: with online convex optimization (e.g., logistic or softmax models for state transitions), the gap between the learned model and truth shrinks at a quantified rate; the bound depends on stability of the online updates and mixing of the underlying process.

- Policy performance: in unconstrained problems, the difference between the learned policy’s long‑term utility and the optimal one is bounded by terms tied to model error; in constrained problems, he gives lower bounds on satisfying the communications constraints as learning proceeds. The punchline: if the true dynamics are representable by the chosen model class, the controller asymptotically reaches optimality. If not, the bounds explicitly show how model mismatch limits performance, an essential dose of realism in ISAC.

From Equations to Air – What the Experiments Show

Pulkkinen validates the approach in multicarrier and multiantenna ISAC scenarios that mirror real deployments:

- Dynamic spectrum coexistence (subcarrier selection): An MBRL agent learns which subcarriers to use or avoid minimizing collisions with coexisting systems. Against baselines (e.g., sense‑and‑avoid, HMM with online Baum–Welch, direct policy OCO), MBRL achieves sub‑linear regret, learning faster and safer in both Markovian and adversarial interference settings. In adversarial cases (where your transmissions provoke jamming), the myopic optimum is no longer global, yet MBRL still strongly outperforms non‑learning and mismatched‑model baselines.

- Co‑design of subcarriers and power under rate constraints: He frames sensing utility via mutual information and enforces a communications MI (rate) floor. The controller first provisions the minimum resources needed for the comms constraint, then opportunistically invests the remaining budget in sensing, an efficient two‑stage routine that exploits concavity in power to keep the optimization fast. MBRL converges quickly; a carefully designed model‑free RL baseline can match or exceed performance only with far larger sample budgets and at the cost of interpretability.

- Learning under partial observability: When high‑quality channel/interference estimates aren’t available, a forward‑correction loss (likelihood‑based) lets the model learn from noisy proxies nearly as well as an oracle that sees the true state. This is a pragmatic fix that keeps learning stable when only coarse measurements are feasible.

- Joint frequency–beamspace allocation (multi‑antenna ISAC): Moving to arrays, he uses an orthogonal beam codebook and GLRT‑based sensing statistics. The pseudo‑myopic (Thompson‑sampling flavoured) controller allocates beams and power to detect and track multiple targets while maintaining user data rates. Visualizations show beams “lock” to users and detected targets, with an adaptive “search” beam to keep discovery alive – a neat, interpretable manifestation of principled exploration.

What Pulkkinen Adds to the Field

- A unifying C‑POMDP lens for ISAC that natively handles conflicts (e.g., sensing vs. rate) as constraints or multi‑objective trade‑offs, rather than ad‑hoc heuristics.

- Practical MBRL controllers (myopic and pseudo‑myopic) that scale to large frequency/beam action spaces without brittle look‑ahead planning, yet retain data‑efficiency and interpretability through learned physics‑aware models.

- Rigorous performance bounds bridging model‑learning error and control sub‑optimality, giving operators clear expectations about convergence speed and constraint satisfaction in live systems.

- Demonstrations in multicarrier and MIMO ISAC that cover coexistence, waveform co‑design, and joint search‑track‑communicate operation, with consistent wins over classical baselines and more sample‑hungry model‑free RL.

Strengths and the Honest Caveats

Strengths. The work is methodologically clean (grounded in decision and control theory), computationally pragmatic (closed‑form or efficiently solvable sub‑problems, histogram/GLM/DNN models chosen for tractability), and deployment‑minded (forward/backward loss corrections; stationarity/mixing assumptions articulated; rate constraints enforced explicitly). It gives ISAC designers a blueprint for real‑time, explainable adaptation—exactly what congested 5G‑Advanced/6G environments require.

Caveats. Like all model‑based methods, performance hinges on model class fit; asymptotically optimal when the model can express reality, bounded otherwise. Pseudo‑myopic exploration is principled but still heuristic relative to full POMDP planning; deriving tight end‑to‑end regret bounds for such large, partially observed ISACs remains open. Finally, practical deployments will need careful engineering of belief tracking (e.g., LSTM vs. filters) and computational budgets at radio timescales. Pulkkinen flags these as fertile directions, including multi‑agent coordination and richer adversarial settings.

Pulkkinen’s thesis is both a profile in rigor and a playbook for practitioners. It shows how to bring learning with guarantees into the RF stack, so a single system can sense, decide, and adapt across spectrum and space, without sacrificing the hard constraints that keep communications reliable. For engineers, it offers implementable controllers and learning recipes; for policymakers and spectrum managers, it points to coexistence strategies that are measurable and controllable; for defence and autonomy teams, it delivers robustness in contested environments where the only constant is change.

Reference

Pulkkinen, P. (2025). Model‑based reinforcement learning for integrated radar and communications systems (Doctoral dissertation, Aalto University). Aalto University publication series, Doctoral Theses 179/2025. https://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-64-2728-7